The hallmark of the EDM scene has traditionally been the rave: a unique type of underground and typically illegal party, where people gather together to enjoy great music, celebrate the presence of each other, and maybe even pop a pill to enhance the evening. Raves are a large part of how EDM has been shaped over the years, and they continue to be the main gathering point for fans—but a disturbing trend has taken hold in the community over the past few years, and it’s fundamentally changing the way EDM is created and portrayed.

For most of its lifetime, EDM has generally been a movement confined to lower-middle class people who are searching for a place of belonging and acceptance. Without resources, it’s easy for people to feel isolated from their peers—if you’re in high school and all your friends want to go see a movie after class but you can’t join because you don’t have the money for it, of course you’re going to feel left out, even ostracized. What better venue to find people in similar situations than a rave—an underground, unpublicized party with little to no cover charge and myriad people from all walks of life gathering in one place to celebrate music, good company and life.

In recent years, however, EDM has increasingly been moving into high-profile nightclubs in big cities, changing the crowd in attendance, as well as the atmosphere of events and even drugs of choice. As ecstasy and LSD are increasingly abandoned for cocaine and alcohol, these settings become more aggressive, fostering fighting and animosity amongst partygoers. Going against the PLUR ethos in this way violates EDM’s roots—in some sense, it’s barely EDM at all, but more of a nightclub scene with dance music.

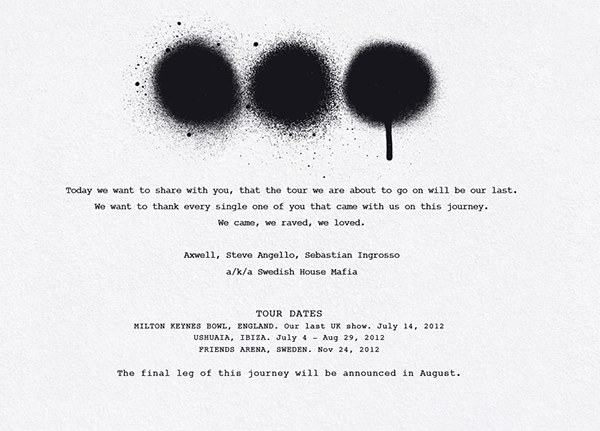

Beyond the movement of raves into nightclubs is the emergence of large production companies starting to take over and legitimize the rave scene. In most places, gone are the days that rave details were kept under tight wraps until the day before or even the day of; when DJs were unknown and big names never played; when they took place in abandoned warehouses or far-flung fields. The traditional rave has been replaced with amped-up versions: world-famous producers are brought in, huge lightshows created, and tens of thousands expected to be in attendance. These high-profile settings also go against where EDM came from in the past.

In his book Techno: An Artistic and Political Laboratory of the Present, philosopher and art critic Michel Gaillot outlines the backdrop of EDM, specifically the techno movement, from various standpoints: political, social, cultural, even economic and philosophic. Amongst his arguments, he presents a position wherein he defends that raves, at their inception, were Dionysian parties—where people recklessly abandoned their normal lives to come together in hedonistic celebration, letting the common thread of music pulse their bodies and put people into a trance-like state of consciousness. Of course drugs are present in any music subculture, but as EDM emerged, they did not play nearly as big of a role as they do now. Now, rather than seeing people gather to hear music and pop pills sparingly, it’s the opposite: at most raves, I don’t even see people dancing, but instead they’re sprawled out on the floor, unable to move due to too much substance consumption. There’s no feeling of camaraderie or symbiotic joy at a rave—it’s a collection of drug users brought together under that goal, rather than a collection of music lovers doing the same.

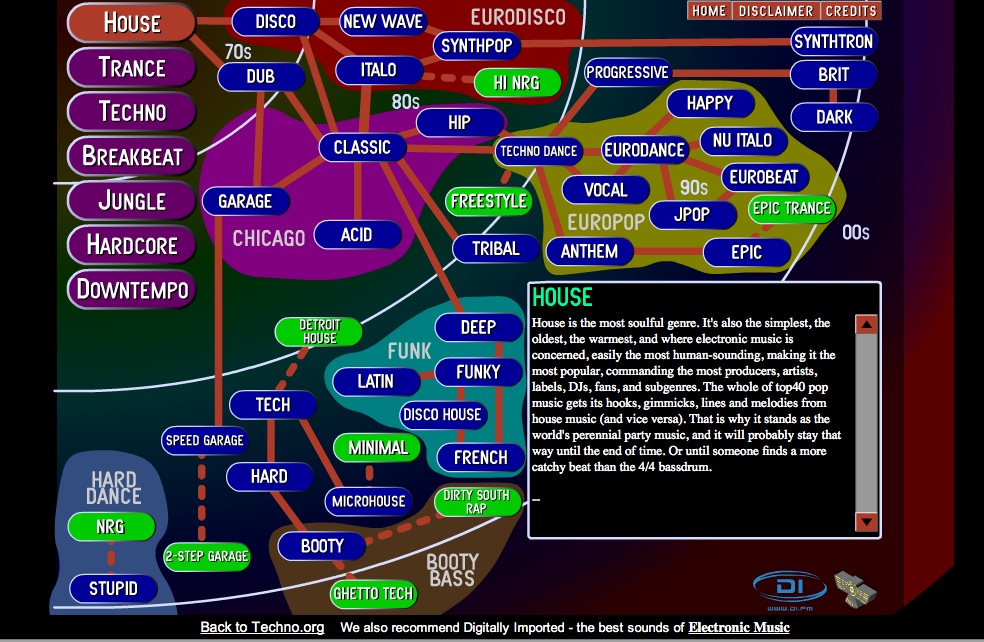

I’m all for progress, so I have no qualms with seeing new styles of music being created and altered all around—after all, EDM is about creation and alteration of existing forms to create something unique. But I’m going to have to point a finger for a moment at a possible cause of this transition: dubstep—or, more specifically, “brostep”. While I understand that dubstep is a legitimate style with a rich history, brostep leaves a bad taste in my mouth. In essence, it’s a reckless amalgamation of other EDM styles—the euphoric buildups of trance, the hard-hitting bass of electrohouse, and frequently even euphoric house or distorted techno vocals—crammed into short, bite-sized chunks of musical insanity designed for the lowest common denominator. Frequently these are high school kids looking to find the most brutal possible music to do drugs to—and this is what I see ruining raves at this moment in time: it’s not about the music, and it’s all about the drugs.

Perhaps the worst offender in this arena is Skrillex: known for being a crossover hit from the dying hardcore scene, Skrillex managed to take what was previously a niche genre with a small but dedicated and pervert it into what is now arguably the most popular style of EDM in the world. The issue I have is that brostep is designed for the ADD listener in mind: it’s short, diverse and homogenous, rarely inventive and musically uninteresting, but its sonic brutality and high-profile producers mask these issues—they’re a smokescreen for boring music, drawing fans in with empty promises.

I’m not saying that EDM is dead—in fact, it’s never been more alive. Aside from dubstep, big-room house and electro are played in small venues and huge arenas alike all across the world, and trance is still a force to be reckoned with in all of Europe. But it’s simply not what it used to be. Unfortunately, I haven’t been alive long enough to have had the privilege to experience raves at their inception, so all I can really speak from is first-hand accounts and textbooks—but that’s given me enough to know that the current scene is completely and fundamentally different from its past. Like I said, I’m all for progression—but I’m reticent to call whatever this is anything similar to what it was.

I agree with your comments about dubstep. I really think it has fundamentally changed EDM and for the worse. But EDM has been played in clubs in asia and europe for a long time now, that’s not something that has changed recently. From my experience it’s almost entirely non-dubstep edm as well.

It is very clear that that the writer of this article has little to no idea of what goes on in the studio, headphones and computers of the most talented EDM artists. To simplify, the artist is creating art. Period. Trying to make the music that they themselves love, frickin’ bangers! It’s never about this “lowest common denominator” or appealing to the “ADD listener”; Skrillex is one of the most ADD people I have ever met btw. If those were the artist’s goals, their pure drive and motivation would probably start to disipate around the 300th hour into the producing process……..so you don’t particulairly like heavy, popular, complex dubstep. Don’t bash it, simply don’t listen to it. I strongly dislike country, but at least I have the presence of mind to respect something the artist is decidating whatever amount of time they have spent towards something that they LOVE doing.

the commodification of the EDM scene is WAY enough incentive for “artists” to want to put together shit music for profit’s sake. don’t delude yourself.

Very well spoken! I completely agree with every single thing you said here