“This project is my way of protecting something that meant so much to me for so long.”

Meet Matthew Johnson. A raver who’s taken it upon himself to preserve electronic music’s culture and memorabilia, namely rave flyers. He started the Rave Preservation Project as a way to share his old flyers with friends and talk about the parties. Then, his friends started adding their collection to the site, and more and more people started sending in their memorabilia, eventually bringing the site to where it is today. The collection is impressively organized, and includes a comprehensive history lesson on rave culture and its origins. Insomniac had the opportunity to talk with Matthew about his non-profit project, and you can click here to read the interview in its entirety.

Read on to learn more about the project, what he’s learned from his collection of over 50,000 unique pieces, and what he thinks about electronic music’s evolution.

How did you get involved in the rave scene?

“My friends at UC Davis took me to my first party in Sacramento in the late ‘80s. I was in high school, and this was when it was really underground (they didn’t even call it “raves” back then). I wasn’t into drinking, and I didn’t really like bars and the pickup scene. Raving was low-key, and everyone was super friendly; it was more like the environment I grew up in (my parents were sort of hippies). I just fell in love with it immediately.”

How many flyers and posters do you currently have?

“Counting duplicates, I’ve got around 150,000 flyers and posters. Counting unique flyers, over 50,000.”

That’s quite a lot to go through.

“Curating everything takes up most of the time. When somebody gives me a box, the first thing I do is separate the flyers it into geographical areas. A lot of times, there’s only a street name and no area code, so I have to investigate. I could spend 10 hours trying to figure out where one flyer is from. If there are any folds, bends or creases in the pieces, I’ll fix those. Then I’ll scan them, organize everything, do post-production, put it up on the website, and add it to the database.”

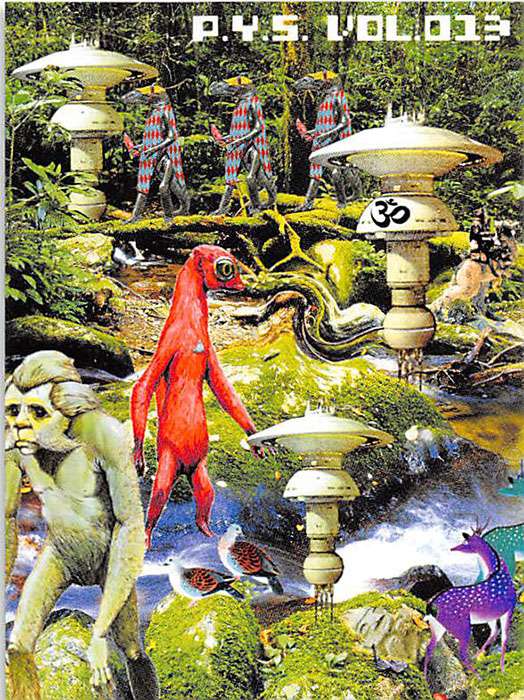

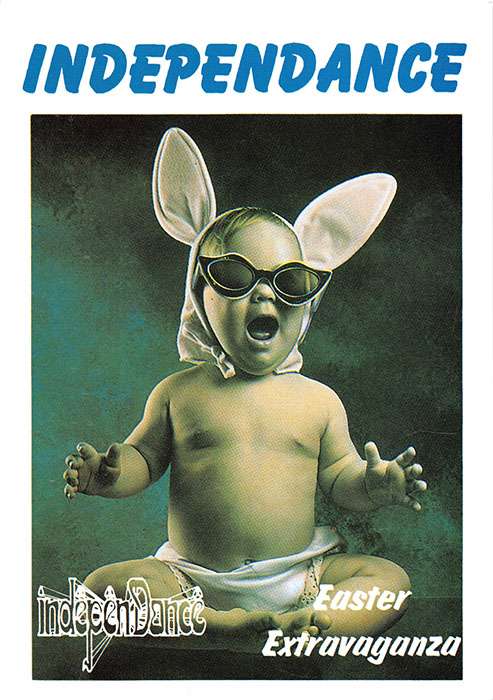

Have you noticed any changes in flyer artwork over time?

“Before you had graphic software like Photoshop, people would paint the flyer design. Then, they would take pictures of their paintings and use a simple program to lay over some text and information about the show. That would be sent to the print shop and become the flyer. So, a lot of the old flyers were paintings.

With the scene becoming mainstream, the flyers became a lot busier. They became an advertising mechanism instead of a source of information. The flyers went from really elegant, nicely designed artwork, to look like somebody threw up, you know? The design suffered because of that.”

You’ve been involved with the scene since the late ‘80s. What would you say about the way it’s evolved?

“When something becomes mainstream, you know the scene is dead. There’s no scene anymore. Now it’s more money-driven, and it’s more style-driven. Back then, people were what they were, and they just happened to go to these things because they were amazing. I have some friends who promoted parties back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s who promote even to this day. Their motivation is the same as it was back then. They love the music, they love the energy, they love seeing all these happy people having a good time; that’s what the core of this is.”

Why do you continue with the project?

“I’m really doing this to give back to a community that gave me so much; that’s really my only motivation. I met the love of my life and most of my friends through raving. I’ve also had so many life-altering experiences due to the scene—more than I can count, really. This project is my way of protecting something that meant so much to me for so long.”