If you haven’t read Part 1 of the series, click here!

In the first part of our series on drugs in dance music culture, we explored the importance of MDMA, more commonly known as ecstasy, as being a significant part of the evolution of thematic elements in the scene. Indeed, MDMA is closely intertwined with dance music culture—while almost all participants in Fendrich’s study said they took ecstasy to “just get high and enjoy” themselves, many users report that they use MDMA to “get into the spirit of the party” (Fendrich et al. 2003:1698), indicating that the general theme of rave culture is enhanced by the drug. But it is not the only drug that is prevalent in the scene. Many rave participants commonly report the use of other drugs both in combination with and separate from MDMA, as well as both at raves and in other locations. Alcohol is the drug that is most commonly reported as being used by members of the dance music community, surpassing even MDMA in popularity, though a majority do not report using alcohol in a rave-related setting (Lenton et al. 1997:1331). The most likely reason for this is the legality and social acceptability of alcohol. Marijuana also has high prevalence in rave cultures; almost all users of ecstasy in a rave setting report using marijuana, both in rave-related and unrelated settings (Lenton et al. 1997:1331). Within the dance music community, marijuana is perceived to be one of the least harmful drugs; many users report smoking it throughout the week, as well as in rave settings (Perrone 2005). Additionally, MDMA has a number of reported side effects associated with the comedown off the drug, including lethargy, moodiness, insomnia depression, and irritability (Davison & Parrott 1997:224); many report that marijuana use during this comedown period softens these negative effects, easing this period of dysphoric feeling often present after consuming ecstasy.

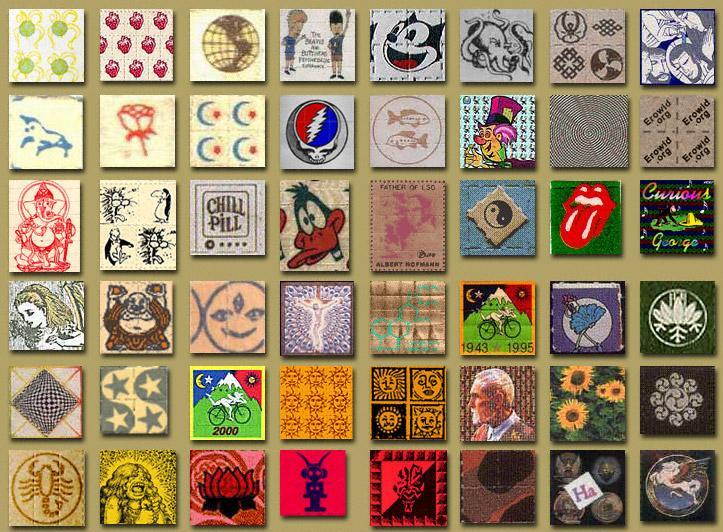

Psychedelics are also quite popular in the rave scene. Some studies show that LSD, a potent hallucinogen prized for its vibrant hallucinations of colors, patterns and thought alteration, is used as much as or even more than MDMA (Lenton et al. 1997:1331). Other psychedelics, such as psilocybin mushrooms and, more recently, research chemicals, are also popular (Lenton et al. 1997:1331). Polydrug combinations of MDMA with these other substances are so popular, in fact, that they have gained colloquial slang terms: a “candy flip” is taking MDMA with LSD; a “hippie flip” is MDMA alongside psilocybin mushrooms; MDMA and ketamine together is known as an “e-hole,” referencing ketamine’s ego disruption effect, known as a “k-hole.” These drug combinations have been popular targets for harm-reduction projects revolving around raves (Lenton et al. 1997:1335).

While many rave participants will stay away from “harder” drugs due to fear or apathy, others will seek them out. In some studies, methamphetamine, an illicit and widely stigmatized drug, is shown to be almost as widely consumed as ecstasy or LSD (Lenton et al. 1997:1331; Fenrich et al. 2003:1696). Drugs such as GHB, or “liquid ecstasy,” and rohypnol, “roofies,” have also been reported in rave settings, lending credence to the problems and concerns surrounding date rape at these events (Fenrich et al. 3003:1696); these drugs, particularly GHB, are dangerous and correlated to overdose, and have also stimulated worry about drug use in the scene.

Polydrug use at raves is extremely common. A large majority of participants in Feinrich’s study—a full 72.8 percent—reported using at least two or more substances in combination (2003:1697). Alcohol and marijuana were the most commonly reported, with cocaine also having a high rate of concurrent use (Feinrich 2003:1697). This can lead to potentially dangerous health consequences: combining a depressant such as alcohol with a stimulant such as MDMA or cocaine can confuse the central nervous system and lead to myriad effects, such as inconsistent breathing or heart problems. Additionally, mixing two or more stimulants together, such as MDMA and cocaine, can lead to an overtaxing of the circulatory system, possibly culminating in a heart attack.

Raves are not the only place where these drugs are found. In fact, many report that, during their last use of a club drug, they were present at a friend’s house or their own home (Feinrich et al. 2003:1697). This use in non-rave settings indicates common participation in “rolling parties,” where many people will gather in one location to hang out and perform many rave-related activities, such as light shows, back rubs and emotional bonding.

Works Cited

Fendrich, M., Wislar, J. S., Johnson, T. P. and Hubbell, A. (2003), A contextual profile

of club drug use among adults in Chicago. Addiction, 98: 1693–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00577.x

Lenton, S., Boys, A., and Norcross, K. (1997), Polydrug use at raves by a Western

Australian sample. Drug and Alcohol Review, 16: 227–234. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187411

Perrone, Dina. (2006), New York City Club Kids: A Contextual Understanding of

Club Drug Use. In Clubs, Drugs and Young People: Sociological and Public Health Perspectives: 26-50. Bill Sanders, ed. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company.

lol citing sources from 1997