Welcome to the first installment of our series detailing the complex relationships between drugs and dance music! Stretching back to the inception of the scene in many areas, drugs are now an omnipresent force within the culture of dance music: at nearly every event, it is possible–and, in many cases, quite easy–to find a wide variety of psychoactive substances available for purchase. In many ways, the use of these substances has substantially shaped the evolution of the subculture–and, in some cases, even the inverse is true. Please note that, while we stress the importance of education when it comes to making personal decisions about drug use, we are not advocating for unsafe and dangerous drug consumption. This series is meant to be informative, analytical, and entertaining, so we hope you enjoy!

“You and I could paint the sky together,” a gentle, breathy female voice serenades from speakers two stories high. “As the world goes by, we’ll go on forever.” The kick drum resonates throughout the huge space, while lights flash and dance from the front stage and from every corner of the room. “Eyes are the windows to the soul.” Bright colors adorn the clothing of most of the people at the event. Nervous excitement is exchanged via glances as people remove pills from pockets and swallow them dry; others take small bags of white crystals from purses and eat the substances inside. The music builds in intensity and volume, and at the drop of the beat, thousands of hands shoot into the air as lasers flash every color of light into the crowd. “Look into my eyes.” The music fades down, giving reprieve to the dancers, some of which dash out of the crowd into the lit areas to search for water and take a break from dancing.

This scene—complete with popular American producer Kaskade’s summer 2011 single “Eyes”—is a common occurrence within rave culture: flashing lights, lyrics filled with themes of love and acceptance, and a communal reaching towards the iconic, almost God-like figure—the DJ—in front of the crowd. Originating from the parties that characterized the Chicago house, Detroit techno and European trance scenes, Kavanaugh and Anderson define raves as “grassroots organized, antiestablishment and unlicensed all-night dance parties, featuring various genres of electronically produced music, populated by large numbers of youths and young adults” (2007:181). Raves began as a cultural movement in the United States and United Kingdom, and continued to grow in popularity throughout the 1990s in both places, as well as abroad (Kavanaugh & Anderson 2007:181).

Like any subculture, raves developed their own idiosyncrasies and principles that guided their character and conduct. Historically, raves have been grounded in a sense of community and solidarity; rave-goers are obliged to follow the four essential tenets of peace, love, unity and respect—PLUR in the vernacular—both while in attendance and outside of raves (Kavanaugh & Anderson 2007:181-182). Several other practices, such as colorful, outlandish dress style, the exchange of back rubs, glow sticks and light shows, communal love of the music present at the show, and respect towards others are also central to rave culture.

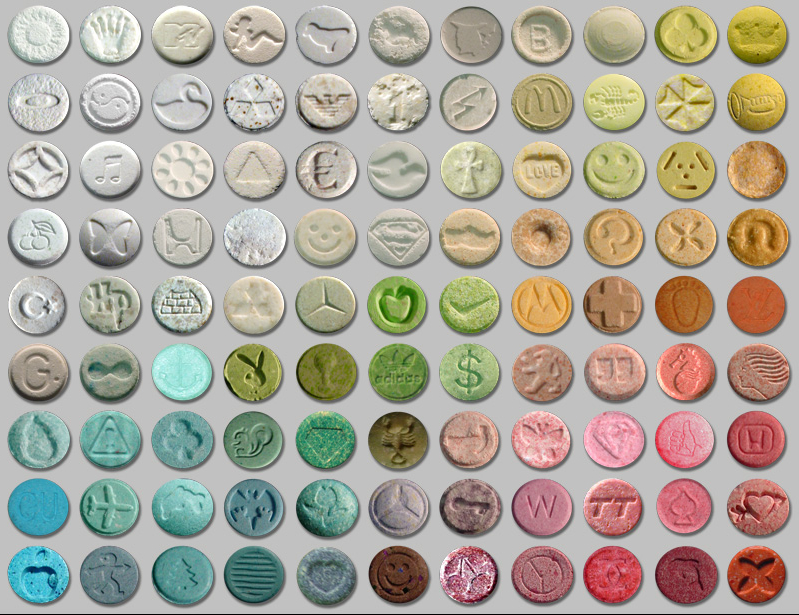

Many of these practices, however, arose from another component of raves: drug use. Drug use has always been consistently linked with dance music culture. The predominant drug associated with rave culture is methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), a drug similar in composition to amphetamine; in its pure form it is an offwhite crystalline substance, but it is commonly pressed into pills. MDMA, more commonly known as ecstasy or E, is a stimulant that produces euphoria, increased energy and confidence, agreeableness, a sense of emotional connection and closeness with others, and an increased appreciation for sound, color, light and touch (Davison & Parrott 1997:222-223). Physiologically, MDMA increases core body temperature, heart rate and sweating propensity, along with dilated pupils and clenching of the jaw (Davison & Parrott 1997:223).

The use of MDMA is central to dance music culture; in fact, many common practices at raves stem from the use of the drug. For example, light shows are frequently seen at raves: during a light show, one person will take small handheld lights or put on gloves with lights on the fingertips and wave them rapidly in complex motions and shapes in front of another person’s face; given that MDMA increases sensitivity and appreciation of light and color and the dilation of pupils allows more light to reach the lens (Davison & Parrott 1997:223), viewers report seeing ‘trails’ of light that enhance the effect of the drug and bring pleasure and euphoria. In addition, many ravers will bring items such as pacifiers, glow sticks or even gum into the party with them; a commonly reported unpleasant side effect of MDMA, similar to other forms of amphetamine, is jaw clenching and tightness (Davison & Parrott 1997:223)—people will chew on these objects to relieve the pressure of the jaw constantly biting down and eliminate soreness in the following days. Even the music played at raves seems tailor-made to those under the effects of ecstasy: many producers of dance music will include white noise, initially beginning at low pitch and volume and gradually increasing, during the buildups of their songs, in hopes that this will pump up the crowd and garner a positive reaction.

The sense of unity and solidarity seen at raves could be attributed to the use of ecstasy in close relation with them. From a public health standpoint, raves have been historically targeted as being toxic venues with massive drug consumption and unsafe sex practices, but Kavanaugh and Anderson (2007) argue that, from a cultural viewpoint, raves are a “safe space” for marginalized youths to gather and find a place to belong. The effects of MDMA lead the drug to the forefront of PLUR raver culture, but it is not the only way that rave attendees form bonds with each other. Historically, dancing itself is a ritualistically rich event that “’synchronize[s]” the emotional and mental states of collective members, as they are exposed to the same ‘driving stimuli’ [music]” (Kavanaugh & Anderson 2007:182). In this sense, ecstasy has a dimension that connects rave participants via another, often unrecognized effect of the drug: MDMA has both psychedelic and stimulant properties, and while the feelings of closeness and emotionality are tied to the psychedelic portion of the drug, the stimulant effects allow for extended periods of dancing and the ability to stay awake late into the night, making dancing itself the forefront of the event (Kavanaugh & Anderson 2007:191).

Works Cited

Davison, D. and Parrott, A. C. (1997), Ecstasy (MDMA) in Recreational Users: Self-Reported Psychological and Physiological Effects. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 12: 221–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1077(199705/06)12:3<221::AID-HUP854>3.0.CO;2-C

Kavanaugh, P. R. and Anderson, T. L. (2008), Solidarity and Drug Use in the Electronic Dance Music Scene. The Sociological Quarterly, 49: 181–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00111.x

Nice article overall, always good to cite sociological research, major props for that. The only thing I would say is that the connection you made between the white noise build ups and drugs could be a lot stronger if you explained it better.

i agree with this. all other parts of that paragraph had evidence and proof, the white noise part sounded like you just threw it in there because you (and i both) know that it does indeed pump us up. good article though, excited about the series.

You recreated 10 minutes of my life when Kaskade closed Digital Dreams with your second paragraph. Bravo.

Fascinating article. Nobody will ever be able to say raves = drugs per se, but the culture like many others is often augmented with those trying to alter their reality. It’s a little utopia (sober or not) and the etiquette of the original rave scene is sadly gone but was something that our culture should encourage not daemonize. If people could be able to abide by “PLUR” as a concept we would be a much better society

Was this a high school project or something?

You should also mention how every other music genre has drug use as well. People just like to ignore that and also ignore how alcohol is a drug too.

flip the page…